Our Islands' Stories.

- lloydgretton

- Apr 2, 2022

- 117 min read

Updated: Dec 7, 2025

1642 And All That

Introduction

In 1984 I was in a taxi being driven to my new apartment in Palmerston North. The European male taxi driver asked me what I did for a living. I answered I was a University student. He then asked me what I was studying. “I said New Zealand history.” He said, “You could use that to measure environmental change". I hesitated and said, “That is possible". I started thinking here was vox populi. Is it possible I could find a common ground of identity with him? So I spoke about my experiences in the History Department of Massey University. How the European and in particular the male part of New Zealand history was as an academic dogma being endlessly denigrated. Its benefits ignored. Its flaws always high lighted with a gleeful satisfaction. There was a campaign to eventually delegitimise our history and our citizenship. He replied. “We won because we were stronger. That is history. None of that matters. They can’t do anything about it.” So I said to him. “Are you telling me, my earnest endeavours to defend your history and legacy are a complete waste of time and money?“ He said, “Yes”. We parted on good terms. But I left feeling deflated and alienated. To quote my own words at the time. “You are sticking a noose around your necks.” A little more than a hundred years before, there had been a major colonial war in New Zealand. You would think that would register with the Kiwis. In that same year, auspicious 1984, the new Lange Labour Government committed two catastrophic errors. They began to corporatise New Zealand and to turn New Zealand into an Orwellian tribal State. We now have the full blown both. The New Zealand media were trumpeting the new Lange Government as “the most educated Government in New Zealand history”. As I had spent the 1970s at Auckland University and encountered the future leaders of the country, I rather wondered about that. And my worst doubts and fears were realised. To paraphrase C S Lewis. “The new University classes have lost common sense and have never acquired a traditional liberal education to replace it.” This blog will attempt to do what the education institutions have failed to do in the last about fifty years. It will highlight the people who actually built New Zealand. How they achieved it, warts and all. So Kiwis can look around themselves and understand how their country was made. And how it can be progressed. I will also try to write a history that has the romance of history instead of just dry facts. 2022 marks the year that a new Jacindastan history curriculum is mandatory in New Zealand schools. This new curriculum will be the New Zealand version of Critical Race Theory. This blog will be an antidote to CRT for New Zealand students and history readers.

Landfall in unknown seas

Evidence for pre Maori settlement

James Cook’s endeavours

Samuel Marsden the flogging Parson and the Missionary

The Treaty of Waitangi that gave freedom of movement and freedom from tribalism to New Zealand

Governor Grey the liberal benefactor, scholar, creator of New Zealand’s first political constitution, and fighter against the Maori kingdom and the HauHau (a cannibalistic genocidal cult).

The Gold Rush

The Struggle for a New Zealand Constitution

1860s-The Decade of War and Millenarianism

1870s-The Boom and Bust Decade

The Danish connection

John Hall

Te Whiti

The Visit of King Tawhiao to Auckland

The First Frozen Meat Shipment to Britain

The Overthrow of the Maori Kingdom

Landfall In Unknown Seas.

Title from an underwhelming poem by a great New Zealand poet Allen Curnow commissioned by the New Zealand Government in 1942 to celebrate the tercentenary of Abel Tasman’s Voyage. It just goes to show the perils of officially commissioned poems.

On 13 December 1642, two navy boats of the Dutch East India Company sighted the north west of the South Island of New Zealand. The name of the yachts were Heenskerck and its armed convoy Zeehaen. Its captain was Abel Tasman. Nothing else of international note happened in the world that day in 1642. The Dutch East India company was thriving enough for the stingy Dutch East India Company directors to send Abel Tasman on a journey of exploration from Batavia capital of the East Indies to the unexplored South and East-lands for new markets and later conquests. The European colonies on the American continent were also thriving and making great progress in civilisation. Not so lucky in England. On the 23 of August, four months before, the English civil war between the Royalists and the English Parliament had started. Western civilisation was in what Time Life Great Ages of Man series called The Age of Kings. The Enlightenment age would not start until another half century. Royal sovereignty ruled supreme and had its dogmas rarely challenged. But the start of the English civil war, a Parliamentary uprising against the lawful Sovereign, King Charles 1, showed all was not politically and spiritually well in Christendom.

Abel Tasman was born in 1603 in the Netherlands. The Protestant Netherlands had rebelled from King Philip 11 of Spain in 1581 and established its declaration of independence. It would not win full independence as the Lord States General until the Treaty of Westphalia in1648. Its charted Dutch East India company competed in the East Indies with the Spanish Catholic Empire. The Spanish royal territories in the East Indies were named the Philippines after Philip 11. So Abel Tasman’s life was filled with the stresses and surges of war. It might have been with a sigh of relief from landlubber troubles that he sailed with his two boats from Batavia in August 1642.

When the two Dutch boats sighted the landmass of the South Island, there were no signs of human habitation. Tasman ordered a gun to be fired at the shore, maybe as a celebration of their discovery of a new land. That artillery fire might have precipitated the tragic events seven days later. The region was well occupied and the Natives were likely hiding and watching the Dutch boats. The Native men were well primed for conflict and this single firing would have been interpreted as an hostile act. From that moment, the fate of the Dutch ships and Dutch sailors were sealed.

Some reflection should now be made on the people the Dutch sailors encountered in New Zealand. Tasman in his journal at first calls them people instead of natives or savages. The Dutch were looking for trade and good relations. Not for Christian evangelical conversion. After the tragic events, he called them murderers. That was somewhat unchivalrous. The Natives were protecting their people and resources from an intrusive sound shattering power. But Tasman lost four sailors in the December twentieth encounter. Sailors on the sea are a close knit community. At least on a yacht and a fly boat.

The native people encountered have been documented in the nineteenth century as Ngati Tumatakokiri. That means literally the descendants of an ancestral chief Tumatakokiri. Since the landing of Captain Cook’s Endeavour in 1769, explorers and officials have been saying in various versions. “Take me to your leader.” As Maori themselves say, their identity is hapu, (community), and whanau (family). Also iwi (bones) as descended from ancestors. A Maori man unless he was forced to be a slave or join the women, took orders from no one. If he was stronger, he might become a rangatira or even an ariki. He was a hard ass, facing at all times imminent death from those who wished to replace him or just sought vengeance from some real or imagined insult. Then he was likely in the pot. Most likely at the moment of the ill timed firing from the gun, the local warriors were primed to drive out the intruders. Maori warriors were probably following the Dutch ships as they sailed around the coast line. When the ships showed signs of embarkation, they were ready for attack with a flotilla of waka, (canoes).

The first encounter on December 18 must have seemed promising to the Dutch. In Tasman’s journal for December 18

“In the evening about one hour after sunset we saw many lights on land and four vessels near the shore, two of which betook themselves towards us. >>> People in the two canoes began to call out to us in gruff hollow voices. We could not in the least understand any of it; however when they called out again several times we called back to them as a token answer. But they did not come nearer than a stone’s shot. They also blew many times on an instrument which produced a sound like the moors’ trumpet. We had one of our sailors (who could play somewhat on the trumpet) play some tunes to them in answer.”

This encounter recalls the first meeting with the space alien ship in the movie Close Encounters of The Third Kind. However the opportunity to signal, ‘We come in peace” had been lost.

The next morning, December 19, a boat dispatched to shore to store water, was attacked by one of the waka. Four of the Dutch sailors were killed with mere (clubs). The waka then fled back to the shore, taking with them one dead Dutch sailor. He was presumably put in the pot after a hard day of excursion and battle. The Dutch then sailed away from New Zealand for good and Tasman named the area ‘Murderers’ Bay'. The next evening Tasman counted twenty two waka at the shore. Eleven paddled to the Dutch boats. One man on a waka was observed to be holding a white flag. “A truce flag? Utu had been exacted for the invasion? However the Dutch had lost men treacherously slain. The waka were fired upon and one man was observed to fall.

The Dutch East India Company were not overly impressed with Tasman’s exploration voyages. A report wrote they wanted a “more persistent explorer”. However the cautious Tasman had made great strides in oceanic exploration. His voyages circumnavigated Australia. He established Australia was not part of the fabled Southern Continent. He suggested New Zealand might be the western part of the Southern Continent. He named New Zealand Staten Landt. Tasman wrote in his journal 13 December. “It is possible the land joins to the Staten Landt but it is uncertain.” Staten Landt as named then is an island at the tip of South America. and was considered might be the northern tip of the South Continent. The Dutch East India Company were certainly ambitious to have the legendary Southern Continent named after their Dutch State which was still engaged in an existentialist struggle with the Catholic Spanish King. Tasman’s exploration legacy remains in his naming of the Tasman sea and Three Kings Islands off the north coast of the North Island. Also Cape Maria van Dieme the westernmost point of the North Island.

In 1643, Staten Land was discovered by the Dutch explorer Hendrik Brouwer to be an island off the Southern Coast of South America. The efficient Dutch cartographers promptly changed Staten Landt in the south Pacific ocean to Nova Zeelandia. That was Latin for new and Dutch for sealand. Zeeland was a province of the Netherlands, of land reclaimed from the sea. The 1642 encounter between the Dutch and the New Zealand people was so disastrous it is pleasant to note both the Dutch and the Polynesian explorers share a correct understanding that New Zealand was land from the sea.

Notwithstanding the condescension by The Dutch East India Company, the Dutch people have taken Abel Tasman into their hearts as a national hero. Many streets are named after him in the Netherlands and there is an Abel Tasman museum in his native village.

In the seventeenth century, oceanic sea voyages were a highly dangerous endeavour. Robinson Crusoe as an adventure moral story, and Gulliver's Travels as satire were early eighteenth century literary classics and best sellers. Robinson and Gulliver were constantly ship wrecked on distant shores with entire crews drowned. Abel Tasman safely brought his boats with small loss of life back to Batavia.

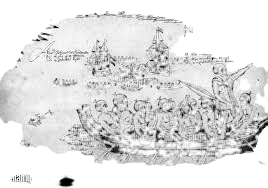

Sketch by Isaac Gilsemans, Abel Tasman's ship artist at Murderers Bay now Golden Bay in 1642.

We can speculate what might have happened if the Dutch explorers had likewise become ship wrecked marooned on the New Zealand shores. Would in the following centuries, reports circulated of a strange fairy blond and tall people in the mountains and remote bush? There is the Maori legend of the Patupaiarehe people. In Wikipedia. Patupaiarehe are supernatural beings in Maori mythology that are described as pale to fair skinned with blonde hair or red hair, usually having the same nature as ordinary people and never tattooed. They can draw mist to themselves, but tend to be nocturnal or active on misty days as direct sunlight can be fatal to them They prefer raw food and have an eversion to steam and fire. Wikipedia refers later to their large well fortified settlements and having calabashes that were heavy to carry away. They did not engage in warfare unless attacked and would flee at a Maori encroachment. They practised weaving which the Maori in their legends learnt from them. Captain Cook in 1769 observed. “Natives used nets woven exactly like our own.”

Evidence for pre Maori settlement

These Maori legends have brought about much alternate scholarly speculation the Patupaiarehe were of Celtic descent who arrived in New Zealand 3000 years ago. If one tries to examine this more realistically when did Celtic populations acquire maritime skills that might in a pre Abel Tasman era have got them to New Zealand? I would suggest via the Irish currachin in the sixth century A.D. The curragh was made of a wicker-work frame covered with hides which were stitched together with throngs. By the sixth century, Ireland was converted to Christianity and there were thriving monasteries and scripture study. Saint Brendan in the early sixth century is legendary for his Irish voyage with fellow monks to the Isle of the Blessed in a currach. In recent history, theories arose that these Irish monks were the first Europeans to reach the Americas. An adventurer Tim Severin in the 1970s demonstrated that it is possible for a currah to reach North America from Ireland.

Could a sixth century currach sail from Ireland in the sixth century to New Zealand? If its seafarers were determined, skilled and lucky enough over a period of years, I suppose they might. In 2013, an Irish couple completed a 15,000 miles sailing expedition from New Zealand to Ireland in a five foot cruising yacht.

What reason would motivate a curragh voyage to New Zealand in the sixth century? To take part in a sea voyage without hope of return. Did something of an environmental nature happen in that century for such a drastic undertaking and who might have done so? In 2018, a medieval scholar Michael M McCormick nominated 536 as “the worst year to be alive” because of the extreme weather events caused by a volcanic eruption in Iceland early in the year, causing, average temperatures in Europe and China to decline and resulting in crop failures and famine for well over a year. This was the coldest decade in the past 2300 years. The Chronicle of Ireland, ecclesiastical records of Irish events from 432-911 AD, record “a failure of bread from the years 536-539”. The Icelandic volcanic eruption spread ash across the Northern Hemisphere, blocking out the sunlight for over a year. ‘For the sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon, during the whole year,” wrote the contemporary Byzantine historian Procopius. The world endured a decade of famine and the Plague of Justinian, the Byzantine Emperor. In Ireland without bread, where was there to go except as in Ireland thirteen hundred years later, out to the ocean? Did a flotilla of curragh led by a millenarian prophet embark to find the Isle of the Blessed? Saint Brendan was in his eighties when he sailed to the Isle. That was the 560s. However Saint Brendan’s voyage was not the first voyage to the Isle of the Bless. Another Saint had done the voyage and told him about it. Saint Brendan’s curragh was in the tradition filled with eighteen monks. So half a dozen curraghs would make up about over a hundred men, women and children refugees. The curragh seafarers were simple fishermen. Only their prophet might have been literate in Latin. His followers knew weaving for their fish netting and their boats. Some were skilled in metal work for their tools. Metal weapons they did not know, having always relied on their Irish Lords and Abbots to protect them. But they were well versed in sailing, fishing and singing Christian psalms in Gaelic. They sing them accompanied with the Irish bagpipes.

In the original tenth century manuscript of the Voyage of Saint Brendan, it is recorded thus.” Brendan and his companions, using iron implements prepared a light vessel, with wicker sides and ribs such as is usually made in that country, and covered it with cowhide, tanned in oak bark, tarring the joins hereof, and put on board provisions for forty days, with butter enough to dress hides for covering the boat and all utensils need for the use of the crew.” This report does not mention a sail. Later the report mentions that with breeze a sail was employed. Otherwise under the commands of their Saint, the monks heaved with the oars.

They sailed looking for the Isle of the Blessed. But every land they encountered was occupied and the sun remained gloomy. Darkness still settled over the world as at the beginning of Genesis. It seemed this was end times as prophesied in the Book of Revelation. They sailed around Cape Horn. As they sailed out into the Pacific, they took with them sturdy roots of the kumara and rats. They learnt in their longest voyages to catch rainwater, and drink their urine, and eat fish, rats and semen as fresh food. Then when they were in near complete despair, and the winds were driving them back down into a chilly environment, they sighted a bountiful land empty of people and even of large animals. At the same time as they landed, the sun began to regain its lustre and light returned to the earth. Their prophet announced a miracle. They embarked and sang their Christian psalms to the accompaniment of their pipes. Here, announced their prophet would be their Canaan, their land not of milk and honey but of teeming bird life, rich vegetation and its seas filled with marine life. They built their huts and their stockades. Their smiths fashioned out of fire their tools. Weapons they did not make. There seemed to be no human enemies and their prophet had taught them to live in peace as like their Irish Saints. They took their currachin out to fish in the sea and the rivers and streams. They were master fishermen. The birds were so plentiful and tame they could kill with stones, wooden implements and traps. They planted their kumara and learnt to eat the edible vegetation. They found out many plump birds could not fly. One flightless bird was larger than a man. As pilgrims, they had traded with the peoples they had encountered but had never fought with, enslaved nor raped them. When they were threatened, they promptly took to their boats and the ocean. Their encountered peoples they traded with their fish and their kumara roots. But their metal implements they never traded. Their prophet made them take a vow to always hide them from the native peoples and to never let them see their manufacturing. If the natives acquired these implements and learnt how to manufacture them, they would be exterminated, said their prophet. They also vowed not to teach the natives how to weave their boats and nets. This skill would take away their fishing resource and trade. Each evening, they gathered together and sang their psalms to the accompaniment of their pipes. The native peoples learnt how to cultivate the newcomers’ kumara and preserved legends of fairy white people who arrived in peace, and spoke a strange language in a hissing sound. That sibilant sound they had only heard before from the reptiles.

Generations passed in their new settled islands that were empty of any other people. When their populations grew beyond their resources, groups departed to the next fertile land. Their prophet died. As only he was literate, his bible was neglected and lost in the bush. Gradually over the centuries, Christianity was lost except for their psalms still sung in their Gaelic. Their Gaelic became more primitive and most of the meanings of their psalms were lost. Eventually their psalms only sang of the sky and earth, and life and death. They carved abstract images of flora and fauna, and non tattooed people.

Then one day, five hundred years’ later, a people from the South Pacific Islands arrived on their shores. The pilgrims fled into the bush and up the mountains. These people were warlike and regularly ate human flesh from their enemies and people they had captured to be their slaves. The new peoples were aware of their existence and called them supernatural fairies. Sometimes in the evenings, they would hear their bagpipes and their singing wafting over the wind. When they advanced to look for them, the fairies disappeared. They called them the Patupaiarehe from the sounds issuing from their bagpipes. The Gaelic onomatopoeia for their bag pipes is pillar uilleann. But a chance encounter with the fairy people, taught the newcomers the skill of weaving nets. The newcomers called their fairies, the tangata whenua, the people of the land. They considered them the first people. But thousands of years earlier, another people had arrived on these shores. They were related to peoples in Europe, Egypt and the Americas who built their astronomy based cities and megalith monuments out of stone and without mortar. However after the last Ice Age, a great flood had exterminated that race in New Zealand. New Zealand's proximity to the South Pole had prevented survivors, unlike other parts of the world. An unexplained embargo forbids archaeological digs of their stone cities until 2063!

It is illegal to tamper with an official document unless signed. Why 2063? Is this an allusion to the centenary of JFK assassination and the CIA invention of conspiracy theory? For more information about the twenty five thousand plus acre Waipoua Northland stone city, read Facebook page: facebook.com new zealand history-the truth 6 May 2020, This may be New Zealand's version of Machu Picchu.

Seven foot high skeletons estimated to be three and a half thousand years old. They are thought to have built the stone cities. Now forbidden knowledge.

The Maori who had now taken over the land thought the fairies fled at the sight of fire and steam. The fairies did not fear them. They feared the gruesome cannibal feasts which they considered an abomination. Their currachs, their nets, and their skills at catching birds, was sufficient to feed them. However the lack of plentiful protein made them small and lethargic. As the Maoris encroached further and further into the land, the fairies’ numbers dwindled. Maoris plundered their settlements and took them away as their slaves. They forced the fairies to learn the Maori language until their own language was extinguished. Descendants from Maori and the fairies produced a fairer complexioned and red haired hybrid population. These populations could not compete with their more aggressive Maori tribal neighbours. The fairies never divulged the secret of metal working. The Maori when they plundered the fairies’ gourds were puzzled at their heavy weight. The Maori never forgot the mournful songs and reed pipes of the fairies. They incorporated them into their own songs. When the missionaries arrived, they took readily and familiarly to the new Christian religion.

James Cook's Endeavours

Between 1642 and 1769, the second recorded visit of European explorers to New Zealand, much was stirring in the Northern Hemisphere. 127 years had passed by. In Great Britain, a King had been beheaded by his own Parliament. Great Britain’s Royalty had been replaced by a Commonwealth and then the old Stuart Dynasty restored. They were replaced by a German dynasty, the Hanovers. Great Britain fought several major European wars and a virtual world war to make an Empire of North America and India. English literature flourished with John Milton with the publication of Paradise Lost. In 1769, the Watt steam engine was patented leading the way to the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century.

In the meanwhile what was stirring in New Zealand? Maori society seemed to have reached an apogee. Tribal battles were fought and there were constant conflicts of utu characterised by stalking and treacherous killings. Judged from an evolutionary perspective, Maori culture could be described as successful. In a cold and wet land without large animals and much nutrient vegetation, their numbers had grown. They were exceedingly fit and healthy. They intuitively understood contagion from contamination and kept themselves clean. Captain Cook in image above praised in 1769 their latrine habits kept distant from their settlements. Their sick and injured they removed to huts to recover or die. Thereby they ensured their own health and fitness. No skulls have been found of Maori over about thirty four years old. By then, the cold climate and battle had ended them. Still it could be reasonably claimed, the average Maori in 1769 was healthier and if not a slave more free than a British peasant and slum dweller in Great Britain in 1769.

Joseph Banks was the naturalist on the Endeavour. In his journal of the voyage, he spoke highly about Maori culture. He thought a few lived to an advanced old age and were their chiefs. He praised their artefacts and land cultivation, the fierceness and rhythmic grace of their songs and dances, their robust health, their pride and courage. Reporting on Maori culture has echoed Joseph's observations ever since. Joseph was the only literary reporter in detail of Maori culture before its Western influence. In some places and times, Maori culture was Hobbesian (nasty brutish and short). In other places and times, it was Arcadian. No metal nor bow and arrow was invented. They are considered the rudiments of civilisation. Maori culture might be called pre urban Aztec. Both the Aztecs and the Maori were compulsive warriors and cannibals. There is a contemporary theory that peoples without fat meat adopt mass human slaughter and cannibalism to preserve their health and their numbers. If the Maori isolation in the world had been longer, would the Maori have turned their villages into cities? Their constant need to be vigilant from attack made all their cultivated skills communal? No Maori scientist could solitary contemplate how to turn a fibre and stick into a bow and arrow, nor sand into metal?

On 25 May 1768, the British Admiralty under King George 111, commissioned Lieutenant James Cook to command a scientific voyage to the Pacific Ocean. The official purpose of the voyage was to sail to Tahiti to observe and record the 1769 transit of Venus. As a British journalist wrote facetiously. “That is what they told their wives.” Tahiti was a byword for the lascivious South Pacific. I grew up on the East Coast North Island New Zealand with Captain Cook as our founding father. Like the heroes of antiquity, he traveled the land naming every bay from an exploit. He was always above reproach. In historical revisionism, he has been called a pirate whose trail across the Pacific Islands is of violence and blood. However even his worst critics do not deny his voyages into the Pacific were a turning point in Pacific islands’ history. Cook was certainly a hard practical sailor. He literally with his cartography put New Zealand on the world maps.

His sailors probably had mixed feelings about him. The eighteenth century was the Enlightenment Age, and the Admiralty’s often highly impractical orders to him reflected that.

The ship under Cook’s command was HMS Endeavour. Officially, she was a British Royal Navy research vessel. She was a full-rigged bark. That meant a merchant ship purchased by the Admiralty. Her previous role had been a collier. Colliers were sturdy coal cargo ships. Like the mythological Greek hero Jason, commoner Cook whose eponymous ancestor was presumably a cook and whose father was a yeoman, embarked with British heroes from the scientific and artistic communities. They represented the new men in England. With the exception of Cook, they were from rich privileged families but without nobility titles. Cook had acquired the status as Captain and commander over them by his cartographic and leadership genius. Cook was already a legend for his cartography for the Admiralty in North America. Officially however as fitted his lowly commoner status he remained a naval Lieutenant. Everyone except his most intractable enemies would always call him Captain. HMS Endeavour embarked from Plymouth Dockyard in August 1768. All the crew were listed on embarkation, except one curious omission. The eleven year old child Nicholas Young. He figures twice in the Endeavour's logs. First for his recorded sighting of the Coast land of New Zealand. Second for his sighting of England on the Endeavour’s return. Was a child employed for his sharp eyes of sighting land? That could be a matter of life and death. The other or second possibility for a sea voyage for many months and a crew entirely of men is somewhat sinister. Nicholas as recorded later was entrusted to the care of the assistant surgeon. There must have been much jubilation and ahoy lads, and sorrow from women folks and children left at shore. One third of the Endeavour’s crew died on the voyage. A record about double that of the average contemporary slave ship on its voyage from Africa to the British colonies. The slave ships had valuable human cargo. The Endeavour at the deck level had hands. The great majority of the mortality on the Endeavour was in the return voyage from Batavia to Cape Town. Cook attributed the deaths to water taken from an island. Several seamen would die on each day. If the sailors had left records of their voyage, they might have by now be calling the Endeavour a death ship. On 20 March 1771, Cook wrote defensively in his log. "Every newspaper in England will write about and exaggerate the sufferings in the Endeavour and not know the attrition rate of twelve months’ voyages from England were as bad or worse than the Endeavour’s three years voyage." However the Endeavour’s voyage’s achievements silenced any public criticism from the newspapers. Cook returned to England a national hero, courted by the rich and famous. What was said in the taverns and among bereaved families is not documented

The Endeavour stopped briefly at Madeira, a Portuguese island in the Atlantic Ocean. At the Madeira tide on September 15, there was the first death. As Cook recorded in his log, “In heaving the Anchor out of the Boat Mr. Weir, Master’s Mate, was carried overboard by the Buoy rope and to the Bottom with the Anchor. Cook blamed the accident ‘owing to the Carelessness of the Person who made it fast” the night before. The next day, Cook recorded. “Received on board fresh Beef and Greens for the Ship’s Company, and sent on shore all our Casks for Wine and Water.” This characterised Cooks revolutionary insistence on greens for his men. Cook didn’t mention how these ship provisions were paid for. I imagine English gold from his cabin. Then there is another curious incident on the next day. “Punished (two sailors) with 12 lashes each, for refusing to take their allowance of Fresh Beef.” British sailors loved their beef, the traditional British sailors’ sea faring diet. Cook whatever else was not a sadist. Were they being flogged for dereliction of duty that led to the fatality two days before? The punishment was light in official eyes at least. Did the sailors agree to it in return for a cover up of the death and a trial back in England that might have brought about their executions?

Meanwhile the botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander were enjoying the home hospitality of the Madeira English Consul. Banks saw no need to mention the tragedy in his journal while he enjoyed the hospitality and recorded the island’s botany. An American colonist sailor on the Endeavour, Lieutenant Gore entertained a fellow colonist twenty year old John Thurman most likely at a tavern on shore. The next morning Thurman woke up to find he had been “pressed” to replace Weir on the Endeavour. The Endeavour was on Portuguese sovereign territory. The Admiralty had the legal right to press gang British subjects into the navy. That extended to subjects of British territories outside Great Britain. In 1769, the North American colonies were restive but still under the Empire of King George 111. Press ganging of American colonists was a sore issue in North America among many other grievances. However press ganging from a foreign nation was of doubtful legality. Thurman could have called on Portuguese subjects to rescue him from the hard seafaring life on the Endeavour. Gore perhaps slipped a drug into Thurman’s Madeira wine and carried him comatose to the port. There with the discreet assistance of other Endeavour sailors he was put on the boat and paddled to the Endeavour. Cook in his journal for the day made no mention of Thurman’s press ganging.

On 19 September at midnight, Captain Cook sailed from Madeira after taking Leave from the Governor that day. The Governor did not appear to know about Thurman. But Thurman’s sloop would surely have been looking for him. Departure at midnight seems rather surprising and conspiratorial. Surely midnight is not a good time to embark from a port unless something or someone was being smuggled away.

In his Saturday 19 November entry in his journal Cook wrote. “Punished John Thurman, Seaman, with 12 lashes for refusing to assist the Sailmaker in repairing the Sails.” 12 lashes appeared to be the standard corporal punishment for small transgressions. Thurman’s transgression seems more like mutiny which was a capital offence. Did the young man need a hiding to break him into his press ganging? In his voyages, Cook kidnapped a number of Natives onto his ships where they were given guest treatment and returned to shore with positive feelings at least according to Cook. But white man Thurman was a sailor. Americans of his class would join George Washington’s army in the American revolution a decade later.

The Endeavour crossed the Atlantic, rounded Cape Horn and anchored in Matvai Bay in Tahiti on April 13 1769. Tahiti was already something of a tourist attraction. In that day’s log, Cook wrote. “We had no sooner come to an Anchor >>> than a great number of the Natives in their canoes came off to the ship and brought with them Cocoa Nuts, etc." Two years before HMS Dolphin had harboured in Matvai Bay. In non woke language, Wikipedia writes. "The first contacts were difficult, but to avert an all-out war after a British show of force, Purea, (a chiefly woman) laid down peace offerings leading to cordial relations.” This would be echoed in Cook’s first arrival in New Zealand. The Pacific Natives were primed for battle with any intrusion. After a bloody encounter, the British had withheld fire and the Natives acquiesced to befriend and trade. In 1768, a French expedition also reached Tahiti and were welcomed. After many delightful adventures soured somewhat by Native thieving, Captain Cook departed Tahiti on 13 July 1769. That was a three month stay in Tahiti. A Cook tour as it were. Polynesian folklore accuses the European exploration ships of spreading venereal diseases on the islands. Legends circulated of Cook’s ceremonial marriages to chieftain women. I have heard a rumour that legends of Cook’s voyages circulated in the Pacific. His name and reputation mythologised to Kupe who first sailed to New Zealand to the discovery cry of his wife, “Aotearoa". Long White Cloud Land. Travellers to New Zealand have seen that cloud formation on the Pacific horizon ever since and that name has been part of New Zealand’s identity.

Observations of the transit of Venus were made in Tahiti. They turned out to be mostly useless. Once the observations were completed, Cook opened the sealed orders, which were additional instructions from the Admiralty for the second part of his voyage to search the south Pacific for signs of the legendary rich southern continent of Terra Australis, (Southern Land). Abel Tasman’s voyage over a hundred years before had fostered its legend. Had Tasman reached Terra Australis in the islands of New Zealand? Eventually Terra Australis the southern land complementing the northern land would be discovered. But as the iced over continent of Antarctica. Cook whose passion was not astronomy must have had his heart leap with joy that he would navigate the Endeavour into the uncharted vast waters of the South Pacific. That is if he hadn’t been tipped off in London of the prime goal of his voyage. The Portuguese, the Spanish, and the Dutch had been the world sea explorers. Now it was the British turn to rule the waves as Britannia.

As the Endeavour sailed south into the colder seas, Cook offered in early October a reward of rum to the sailor who first sighted land and promised that that part of the coast of the land should be named after him. When the Coastline of the North Island of New Zealand was sighted by the twelve year old cabin boy Nicholas Young from the masthead on 6 October 2 pm, he was awarded the rum. How the boy disposed of it is not known. 6 October 1769 goes down in world history as the first English sighting of New Zealand. Official celebrations or lamentations have marked that day as the beginning of New Zealand modern history. Cook named on his chart White Island that was sighted on 1 October. He named it after its constant white plumes of smoke and steam. Curiously, Cook made no mention of the discovery of White Island in his journal. The sighting of White Island was therefore the first British discovery of New Zealand. Cook sensibly declined to land on the island. Cook records in his journal for 1 October. “One would think that we were not far from some land, from the Pieces of Rock weed we see daily floating upon the water.” He must have been aware that the coastline of New Zealand was near at hand. Therefore he had the boy posted up in the masthead. However, his first record of land sighting in his journal would be a landing. He would eclipse Abel Tasman with his much inferior boats from the start. Nor would he make Tasman’s error of firing a gun at the shore. The Endeavour would sail quietly into the shore and its boats would land intentionally in peace. Under the maritime law of discovery, after the first landing, Cook would claim the land for King George 111. Abel Tasman’s failure to land on the shore and so to claim New Zealand for the Dutch Lord States General, Cook would not emulate. The Maori name for White Island is Te Puia o Whakaari. The smoking volcano. As the Endeavour sailed towards the island, they saw a long white cloud over the horizon as in the Maori legend of Kupe’s wife’s sighting of Aotearoa, Long White Cloud Land.

On 8 October, the Endeavour in a day of gentle breezes and clear weather sailed into a bay and anchored before the entrance of a river. Cook went ashore with a party of men in the pinnace and yawl accompanied by Mr Banks and Doctor Solander. They landed on the shore. There they had a fracas with Maori whom Cook called Indians. Two warning shots were fired by the coxswain. The Maoris after the second shot continued to charge the pinnace. A third shot was then fired, and a man dropped dead. According to Banks, just as the man was going to throw his spear at the boat. Banks recognised him as the chief. They promptly returned to the ship. Banks described the shot man. “He was a middling sized man, tattowed sic on one cheek only in spiral lines very regularly formed. He was covered with a fine cloth of a manufacture totally new to us.” The identity of the sailor who fired the fatal shot was not given in the Endeavour’s journals. Captain Cook’s report of the fatal encounter is corroborated by other eye witness journals. Cook was in a tricky situation. The safety of his ship and crew was paramount. But he was also bound to the strictures of the Admiralty. His secret signed letter instructions from the Lords of the Admiralty, ordered him, “With the consent of the Natives to take possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the Name of the King of Great Britain.” The letter continued to instruct Cook to take possession of His Majesty of any other land not discovered by Europeans.” This letter was worked out either by a committee or was Machiavellian. This was the Enlightened age where might clashed with universal humanism.

The Maori appeared to have no historical memory of Abel Tasman’s foray 127 years earlier. In the earliest written reports in1836 of their observations of the Endeavour and crew, they thought the Endeavour was a bird and the British sailors malevolent Atua (Gods). These Atua by a look could make them ill. Interest in history for its own sake is a civilised pursuit. There were no souvenirs to record Abel Tasman’s visit. The fallen Maori chief was remembered as Te Maro. His memorial overlooks Gisborne city. Captain Cook’s statue is in the Gisborne museum as forlorn as the Ancient Mariner.

The chief's sartorial style certainly eclipses the Maori at the Abel Tasman encounter as shown in earlier image above. They appear to have no tattoos. This portrait was drawn by Sydney Parkinson the artist on the Endeavour in New Zealand in 1769. Sydney Parkinson died on the voyage back to England..

After two more disastrous encounters involving taking of Maori life, The Endeavour departed from the Bay with a parting shot from Cook in his log, “I have named Poverty Bay, because it afforded us no one thing we wanted”. However there were two positive developments. Three kidnapped Maori were returned to shore, full of glad tidings about their abductors. At least the Endeavour crew thought so. Tupaia the Endeavour’s chiefly guest from Tahiti, was discovered to share a “perfectly understood language” with Maori. Tupaia died on the voyage back to England.

The rest of the Endeavour’s voyage in New Zealand was relatively plain sailing. No more lives were taken. After six months, charting the New Zealand coast, Cook and his crew resumed their voyage westward across open sea.

The legacy of the first Endeavour voyage belongs to the ages. The legend of Terra Australis was finally squelched. Cook’s map making, with only two inaccuracies in New Zealand, made the South Pacific part of world history and geography. The Endeavour’s scientific reports were a magnum leap in world knowledge. Cook back in England was touted as one of England’s greatest sons. His ocean explorations would continue for another decade until his murder in Hawaii in 1779, thereby demonstrating the fate of those who live dangerously.

Captain Cook's original 1769 physical map of New Zealand.

A foot note to the press ganged American John Thurman. On 3 February on the voyage between Batavia in the Dutch East Indies to Cape Town in the Cape of Good Hope, Cook wrote in his log. ‘Departed this life, John Thurman, sailmaker assistant.” In every other Endeavour death, except this one and the one immediately after, Cook dutifully reported in his log cause of death and sometimes a few details. Thurman had been flogged first for rebellion, and then for theft in Tahiti. The explorations of the Endeavour were over, and they were on their way home to England. Was Thurman threatening to take action against Cook in London for press-ganging in Portuguese sovereign territory? Thurman was from New York where Republican and liberty ideas wafted about freely and would lead soon to the American revolution. I recall my father once saying there was a sailor on the Endeavour who took legal action against Cook for a flogging on the Endeavour. Had my father picked up on a distorted story of the Thurman saga? Was there a cover up about deplorable John Thurman on the Endeavour and in the sea? The two seamen flogged at Madeira, Henry Stephens and Thomas Dunster both survived the Endeavour voyage and might have owed a debt to Cook from the hangman.

Samuel Marsden, the flogging Parson and the Missionary

Samuel Marsden was a small child when the Endeavour returned to England. A Yorkshire man from the artisan class, Marsden by diligence and study became in 1800 the senior Church of England chaplain in New South Wales. He would hold that position until his death in 1838. In 1800, Georgian England and her remaining colonies after the American revolution, were ever upward. 1800 marked the appointment of Napoleon as First Consul of France and the first smallpox vaccines invented by Doctor Jenner in 1796 were being delivered to a vaccine hesitant public. Marsden grew up under the shadows of the American and French revolutions. Cook’s voyages opened up the world to new adventures for the adventurous. Despite or because of his Wesleyan family background, the Church Of England beckoned the youthful Marsden to a missionary life at the far end of the British territories in historic Terra Australis. Cook’s Endeavour voyage to New Zealand had finally debunked the Southern Continent. Terra Australis with New Zealand included would become Australasia. That is Southern Asia. Without New Zealand, she would become Australia. The British colony of Australia was officially a 12 year old frontier and growing New South Wales. New Zealand was where there be savages and cannibals. In the late 1700s, the Maori population discovered by Abel Tasman in the Three Kings Islands had been exterminated by a Maori war party. Three Kings Islands named after the Three Magi at Jesus’s birth now lay silent except for the birds, the witnesses to Maori tribal pagan ferocity. Marsden would pledge his life’s mission to end their darkness. My History professor in the pre Woke era once remarked. The Spanish converted the Natives, the French turned them into Frenchmen, the Dutch and Germans worked them, the British civilised them. Or at least they all tried that.

I grew up with the image of Samuel Marsden as the New Zealand Saint Augustine. I well recall his large picture in my New Zealand history school textbook. Later I was surprised to learn of his infamy in Australia. In Australia, Samuel Marsden is a byword for sadistic floggings and convict labour exploitation. The Australian children’s author John Marsden has spent his life apologising for their shared kinship. A Maori reggae band have named themselves the 1814 in celebration of the first recorded Christian service performed by missionary Samuel Marsden in New Zealand. As far as I know that has not aroused cancel culture in Australia. Marsden’s victims were always white deplorables.

On his farm at Parramatta outside the Port Jackson (Sydney) settlement, Marsden as a chaplain and a Magistrate prospered as an innovative sheep farmer, employing convict labour. As a Magistrate, he won notoriety as “the flogging parson". The English were notorious as floggers. Voltaire had commented about his time in England in the 1720s. He was impressed with the English Constitutional Government and rule of law, instead of the capricious Government of his native France. But the English punishments after proper legal rulings startled him. In his 1759 novel Candide, Voltaire referred to the contemporary public execution of a defeated English admiral. “Pour encourager l’autres.” “To encourage the others.” English legal principles and practices had not reformed in the years between Candide and Marsden’s Magistracy. Good Anglican Christian Magistrates ordered skin flying floggings of convicts that would shock any firm conservative today. However Marsden kept a soft spot for Maori chiefly visitors to his farm. They were “the noble savages” of eighteenth century cultural fashion. God was waiting for Anglican missionaries to convert their benighted souls to Christianity. After the Endeavour exploration in New Zealand. three decades before, exploration European ships had visited New Zealand and had had friendly and beneficent relations with the Natives. In 1769, a French ship the St Jean Baptiste under Captain De Surville had voyaged through New Zealand. They were voyaging in New Zealand at the same time and nearly sighted each other but Cook either didn’t find out or kept it secret. News about the Endeavour must have traveled fast in New Zealand. Wherever the European ships traveled they were met with smiling Natives, eager to trade and to fornicate with the more than willing sailors. De Surville however ended his time in New Zealand with burning a Maori village after accusing them of theft, and kidnapping a chief. The St Jean Baptiste sailed away to South America with the chief. The chief died on the voyage. The French were enamoured with “the noble savage” on a more philosophical and literary level rather than British practical humanism.

However on one occasion, the British were not above kidnapping two Maori chiefs to Norfolk Island to teach its convicts how to weave flax. This was done in 1792 by a British captain with an elastic view of official orders to invite Maori to Norfolk to teach the skill. One of the chiefs in Norfolk drew in chalk a Maori map of the North Island. They were treated akin toroyalty and returned seven months later to their New Zealand homeland. That initial bad event ended harmoniously. However the attempt to teach flax weaving to the convicts failed. The chiefs explained they didn't know how as that was woman's work.

The South and North Islands as developed from the original chalk drawing. They show the Maori metaphysical world.

In 1772, French Captain Du Fresne's two ships’ crews were massacred and eaten at the Bay of Islands. I recall my female University teacher carefully explaining they more or less deserved that for desecrating cultural and resource areas, and overstaying their welcome. She had reasonable points although she would be no doubt very squeamish if confronted with a cannibal feast.

That shocking event made New Zealand for many years a byword for savage treachery and cannibalism. Church missions kept well clear of New Zealand and only European sealers and whalers seasonally inhabited and traded on her shores.

By 1800, a small community of Europeans had formed in the Bay of Islands, made up of flax traders, timber merchants, seamen and ex-convicts. Some convicts escaping the law also. They serviced the ships that regularly landed in the whaling and sealing trade. Maori adventurers worked their way as sailors to New South Wales. There some encountered Marsden at his Parramatta farm. The most distinguished was Ruatara. He spent most of his life in the Bay of Islands. Ruatara left New Zealand still likely a teenager as a crew member on a whaling ship. His great ambition was to meet King George 111. He spent the next four years serving on whaling ships. In the rough conditions of ships, he received both kindness and beatings. Marsden was returning to Australia from England in a convict vessel when he discovered Ruatara. The chief was ill, half starved and neglected. He had reached the English shore but had been forbidden to land and achieve his cherished goal, meeting the King. By now Maori were no longer a novelty and curiosity. Marsden cared for Ruatara and supplied him with clothes. When the convict ship landed at Port Jackson, Marsden took him to his Parramatta home.

Ruatara the great brown hope. The man who brought Marsden and wheat cultivation to his Northland people. In 1814, while Europe lay in a temporary respite from war, Marsden, the great white benefactor delivered the first recorded Christian service in New Zealand on 25 December Christmas day. Ruatara's death from a fever two months later, made him considered a martyr to the Church of England. Ruatara's uncle, Hongi Hika turned the dream of Marsden and Ruatara into a nightmare trail of musket wars throughout the North Island, and a slave Empire. According to New Zealand's first historian, A. S. Thomson, Hongi ended his days entertaining his compatriots by whistling through a musket bullet hole in his lung.

"How do you do, Mr King George," said Hongi Hika with a bow to the English King.

After the death of Ruatara, Hongi took his place as protector of the Christian mission. He expanded agriculture and trade with ships and established more missions. However conversion to Christianity was almost non existent. The new missionary settlements discouraged the trade in muskets. However Hongi always lusted for them. The muskets tipped the balance in Maori warfare. Gun fuelled rampages replaced the tao, the war spear. Hongi's war parties became feared throughout the North Island as the bullet men, the Nga Puhi. They roamed as far as East Cape and Bay of Plenty. Thousands of slaves were taken back to the Nga Puhi territories in Bay of Islands. When I was growing up in East Cape, a hill overlooking our home was reputed to be the descent of the Nga Puhi into Hicks Bay. Nga Puhi were looked upon with negativity by the locals. The slaves, men and women, were put to work on plantations that grew the new crops of potatoes to be traded with the ships for more muskets.

In 1820, Hongi Hika with the New Zealand missionary Thomas Kendall sailed to England. He spent five months in London and Cambridge. His chiefly tattoos were a public sensation. He met King George 1V who presented him with a suit of armour. He would wear this in battle in New Zealand, arousing terror. In England he assisted Professor Samuel Lee in writing the first Maori-English dictionary.

Missionary Thomas Kendall meets with the chiefs Waikato and Hongi Hika

Thomas Kendall was the next generation of New Zealand missionaries. To him lie many honours and a customary disgrace with a Maori woman.

A son of a Lincolnshire farmer, Thomas was born in 1778. After an undistinguished life as a school teacher and tradesman, he got the evangelical calling in a London chapel in 1805. In 1808, he decided to become a missionary. He was thirty years old. Revolutions are customarily started by men in their early thirties. They are old enough to be mature and lead youth. They are young enough not to be disillusioned and fear danger. The Anglican Church Missionary Society was in that era a powerful organisation with allies in high places including Colonial Secretaries. In our secular now Satanic age, the influence of evangelism upon nineteenth century English society is difficult to imagine. One should read a present day evangelical tract as a relic of the literal beliefs and sentiments that drove the actions of the British Colonial officials over pagan lands. By the 1860s, a new scientific and materialist age replaced it with Darwinism and social reform causes.

The Church Missionary Society had adopted in the early 1800s a new policy of sending lay preachers with practical skills to teach Native peoples English civilisation. They might be enticed into Anglican Christianity that materialistic way instead of being persuaded by biblical texts that Jesus was the son of God who rose from the dead to give ever lasting life etc. Then the Native peoples would send their children to the mission schools to be inculcated with Anglican doctrine. Evangelical Christianity had so far been singularly unsuccessful in pagan lands. Natives were converted and at the next pagan ritual dropped Christianity like they might drop their European trousers.

A mission to New Zealand was being promoted by Samuel Marsden in New South Wales. In 1809, William Kendal was chosen to head the first mission with fellow lay preachers William Hall and John King. Kendall and his family left for Port Jackson in 1813. In 1814 Kendall and Hall took Marsden's boat on an exploratory journey to the Bay of Islands. They met Maori leaders including Ruatara and Hongi Hika. These two Maori leaders returned with Kendall to Australia in that year. The Governor of New South Wales Macquarie gave permission for the foundation of the mission. and in same year appointed Kendall as a magistrate. Under the proclamation of the Governor, Kendall was to work with local Maori chiefs in protecting the Natives from unrestricted immigration and kidnapping. The legality of the proclamation was unclear except as an evangelical and humanitarian issue. Kendall joined Marsden at the next visit to New Zealand in time for the legendary 1814 Christmas service. Marsden returned to New South Wales and Kendall diligently set out to learn the Maori language. By the next year 1815, the year of Waterloo, Kendall had written the primer A Korao No New Zealand. As Wikipedia put it,"This was the first book written in Maori". 200 copies were printed in Port Jackson by Marsden in same year.

After five discouraging years in New Zealand with scarcely a sincere convert but a thriving farming and trading mission, Kendall returned to England with Hongi Hika on a whaling ship. The Church Missionary Society had not authorised the visit and with non Christian charity disapproved. After seven years in the Antipodes, Kendall was likely homesick. That affects most expats. Kendall was ordained a priest in New Zealand in same year 1820. Kendall worked with Professor Lee and Hongi Hika in Cambridge. Kendall's understanding of the Maori language structures formed the basis of: A grammar and vocabulary of the language of New Zealand. Hongi Hika's Northland soft consonant pronunciation has been the standard Maori ever since.

The caption reads. "Students at Cambridge or Oxford circa 1820 play practical joke on their Professors." I don't think they played that on Hongi Hika.

Kendall had British Israel beliefs that the Maori were descended from the Ancient Egyptians. Kendall and Hika traveled to Port Jackson after five months in Great Britain. In Port Jackson, Hika traded his English society gifts for 500 muskets, powder, ball, swords and daggers. Hika returned to New Zealand as a conqueror and slave master of much of the North Island in the Musket Wars.

James Busby The Man of War Without Guns

In 1831, Northland chiefs dispatched a letter to King William of Great Britain. He was the uncle of the child Princess Victoria. It was ingratiating with a subterfuge of enticement and threats to win the favour of the British Crown. The Northland chiefs, (Nga Puhi) were facing the threat of revenge (utu) from the victims of the musket wars. They too now possessed large quantities of muskets that outnumbered the Northland tribes. The evangelism of Colenso and the Williams brothers had ostensibly converted many Northlanders to Christianity. They had liberated their slaves who had returned to their tribal homelands as their first Christian missionaries. Would the Nga Puhi receive Christian forgiveness or utu? The Northland chiefs were uneasy.

The letter was composed in the long winded style of Maori oratory. But its English form and reverence showed the hand of a Northland missionary, likely Colenso. The King "was the great chief of the other side of the water." ... "It is only thy land which is liberal towards us. From thee also come the missionaries who teach us to believe on Jehovah God and on Jesus Christ his son." There had recently been sighting in Northland of a French ship. That made the chiefs nervous about utu for the massacre of the French ships' crews in 1772 almost sixty years before. The Maori expected utu for every transgression or slight. They might be now Christians but utu characterised their upbringing. The letter continued. "We have heard that the tribe of Marion, {the name of the French captain in the 1772 massacre} is at hand coming to take away our land, therefore we pray thee to become our friend and the guardian of these islands, lest the teazing sic of other tribes should come near to us, and lest strangers should come and take away our land." The letter concluded with a veiled threat.' And if any of thy people should be troublesome or vicious towards us , for some persons are living here who have run away from ships,) we pray thee to be angry with them that they may be obedient lest the anger of the people of this land fall upon them. "

The Colonial Secretary replied in a salutary letter. He wrote James Busby would be dispatched as His Majesty's Resident. The letter concluded with reference to the:

{British Resident's} protection to the inhabitants of New Zealand... to extend to your country all the benefits which it is capable of receiving from its friendship and alliance with Great Britain."

James Busby was born in Edinburgh Scotland in 1802. His father was a mineral surveyor and engineer. That put the Busby family into the class of Scotsmen on the make. Scottish independence had been lost in the Union of the Kingdoms of England and Scotland in 1707. Their Sovereigns would follow the English dynastic line in London. But the romance of history in the United Kingdom would be primarily Scottish. The Scots are accredited with building the British Empire with their canny practical skills. One might unkindly say that was their thanks for their material gain but loss of independence. James Busby studied viticulture in France before accompanying his parents to New South Wales in 1824. Viticulture was his first passion. He is regarded as the father of the Australian and New Zealand wine industries as he introduced to the Antipodes from France and Spain the first vine stock. His reports on viticulture and other pressing colonial issues impressed the Colonial Office. His report on the condition of New Zealand gained him appointment there as British Resident. The letter of the Northland chiefs carries a hint of the environment in Northland that gained its sea port Korakoreka the name of "the hell hole of the Pacific" or "Gomorrah the scourge of the Pacific". European settlers in Northland and elsewhere numbered only a few hundred. But Korakoreka had an itinerant population sometimes of thousands of whalers, tavern keepers, hangers on and sex workers. For the whalers on recreation there wasn't much else to do except drink and fornicate. That naturally shocked God's workers. God was a Protestant pious Englishman with sometimes temptations.

A British Resident was an official appointee in foreign territory who carried no magisterial powers. He was a diplomat without an Embassy who represented the interests of the British Government. The Governor of New South Wales Richard Bourke directed Busby to protect "well disposed settlers and traders," to prevent atrocities by Europeans against Maori, and to apprehend escaped convicts". No mention about the whalers. Their master was their captain. Everyone quickly became disillusioned despite the ceremonial welcome to Busby in Northland in 1833. The Maori called him, The Man of War Without Guns.

In 1834, twenty five chiefs gathered at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands in Northland. Missionaries, settlers and captains of thirteen ships also were present. The official British Resident Busby made a speech and then asked each chief to come forward in turn and select a flag from three choices. A Church Missionary Society flag based on the St. George's Cross won with twelve votes. Busby declared the chosen flag the national flag of New Zealand and had it hoisted on a flagpole to a 21-gun salute from HMS Alligator.

The first New Zealand official flag. The original version in 1834 had a black border. This flag has a chequered history. The version we see above was designed in 1839 in the New Zealand Company ship Tory whose passengers founded Port Nicholson (Wellington). This Wakefield settlement declared allegiance not to the new 1840 Government at Waitangi but to the 1835 Busby created Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Niu Tireni (United Tribes of New Zealand ) under this flag. In 1840, the Port Nicholson settlement elected New Zealand's first municipality. In same year 1840, a detachment of thirty soldiers and six mounted police under the orders of the new Lieutenant Governor Hobson arrived on a British warship at Port Nicholson and tore it down. In the uprising against the Covid regime in 2022, it figured prominently as a dissident European and Maori symbol. Again, it was torn down in Wellington by the police in same year. That goes to show the State quickly replaces its kindness with fury when its legitimacy is challenged.

Baron De Thierry. The French revolution refugee and adventurer. His escapades in Europe and the Pacific islands included dodging debts and raising a militia in Tahiti. He met Hongi Hika at Cambridge College and arranged with Kendall to buy on his account forty thousand acres at Hokianga in Northland for thirty six axes. He tried to exchange his bogus land deed with the Dutch and later French Government in return for being appointed the Viceroy and Governor of New Zealand. He alarmed James Busby, the British Resident in New Zealand and the missionary community by issuing manifestos in Tahiti stating that he intended to establish his authority as sovereign chief of New Zealand by force. This prompted the energetic British Resident to establish Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Niu Tireni (United Tribes of New Zealand) to resist a French invasion. We may laugh at a burlesque. But this was twenty years after Waterloo ended French revolutionary hegemony over Europe. The parallel would be a NeoNazi invasion and Government in New Zealand. In 1835, there was no telegraph in the South Seas. He arrived in New Zealand with his ragtag colonists in 1837 and was granted by Northland chiefs eight hundred acres at Hokianga. His colonists rioted and scattered at the dismal prospects. Thierry tried to make do on his plantation and desperately advertised in France for more colonists. His final hopes were dashed by the extension of British territories and the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand in 1840. He later migrated to Auckland and became a music teacher and piano tuner. In the rising prosperity of Auckland, he became a friend of Governor Grey and Catholic Bishop of New Zealand Pompallier, and a modestly successful merchant.

Navy officer and New Zealand's first Governor. William Hobson. With Baron Thierry, he lies in an Auckland cemetery as the unheralded father of Auckland. Another pioneer John Campbell has his statue in Auckland as the father of Auckland in less contentious times. William Hobson was born in 1792. That made him a contemporary of Thierry as born in the shadow of the French revolution. He was born in Ireland and grew up in an Anglo-Irish family. His father was a barrister. That gave him a breeding and mental outlook that paralleled C S Lewis. In 1803 at the age of eleven, like Nick Young, he joined the Royal Navy. To abandon your eleven year old child to the navy sounds incredible. William was three years below the legal age to join the Navy. The nineteenth century British navy was proverbially known as ruled by rum, bum and bacca. Twentieth century variations called the Navy tradition as rum, buggery and the lash. The lash was not a relic in the eighteenth century. However Hobson shone in the Navy and they educated him to his middle class level. He served in the Napoleonic war and by the time he was twenty one was a first lieutenant. From 1822 as a lieutenant commander, he chased pirates and twice was taken prisoner by them in the Caribbean. His capturing of pirate vessels earned him the name Lion Hobson. His seafaring adventures were a British tradition that went back to the privateer or pirate Sir Francis Drake in the sixteenth century. His life story and especially his adventures in the Caribbean became the source of a popular 1833 novel. Tom Cringle's Log by Michael Scott. That was praised as "a most excellent sea story" by the poet Samuel Coleridge.

In 1834, he obtained a Royal naval commission as captain to the East Indies on HMS Rattlesnake. His surveying of the Australian coastline gave the name Hobsons Bay.

In 1837, Hobson sailed on the Rattlesnake to the Bay of Islands to settle tribal disputes at a request from Busby. On his return to England in 1838, Hobson submitted an official report on New Zealand in which he proposed establishing settlements "factories" of British sovereignty over the islands as in Canada. New Zealand now was in international law ,The United Tribes of New Zealand with its own flag. The United Tribes of New Zealand had never assembled again after its foundation in 1835. The tribal leaders did not seem to know about it. But now the British authorities, somewhat hoisted, had to tread warily in New Zealand as a foreign power. In 1839, Hobson was appointed lieutenant-governor under the Governor of New South Wales Sir George Gipps, and later that year as British consul to New Zealand. In New South Wales he was ambiguously deputy to Gibbs. In New Zealand he was the official representative of a foreign power. However the day after his appointment as Consul, the British Colonial Secretary, Marquess of Normanby left no doubt with his detailed instructions to Hobson that he would be the great white chief and peace maker in New Zealand. He was directed to purchase land "by fair and equal contracts". The independence of the United Tribes was reaffirmed. However there was no suggestion that the European settlers lie under the government of the United Tribes chiefs. Such a thought would not have entered any European's mind in the nineteenth century. Rather, the land purchased from the chiefs would form settlements of British law and industry. Their industry would procure capital and labour to support a new British colony. But there was still the legal and practical hurdles of the United Tribes. Their legal existence had to be extinguished. The tribes had to be pacified. Having taken the tentative steps into a new colony in the South Pacific, the British authorities would move fast.

Marquess of Normanby. He is the unheralded father of civilised New Zealand. His clear instructions to Hobson laid the foundation for the Treaty of Waitangi. Normanby bears a distinct resemblance to Byron. Both were authors. Both were House of Lord members. Normanby was a novelist. Byron was a poet. Byron mythologised Greece, Normanby mythologised New Zealand into Arcadias they recalled from their public school days.

It is an appropriate time now, to reflect upon the contemporary culture and history of the soon to be rulers of New Zealand. In New Zealand, the British Crown was a Tory and sometimes Whiggish English Squire. It was fiercely hostile to radicalism and strongly evangelical. It was also pragmatic when confronted with intractable reality. New Zealand would be a testing time for its talents.

In Great Britain, 'the rights of Englishmen' was a rallying cry the British upper classes could never publicly repudiate. It resonated with ancient English traditions of liberty. In the nineteenth century it had acquired further unsettling meanings. The stage coach tempo of life of Dickensian England was fast losing its reality to a new more anonymous industrialised age. Factories and railway lines were devouring the country side into the poet Blake's Satanic Mills. This was the Reform era. Great Britain was being reset into a new normal and the common people had no say unless they rebelled. In 1832, the British Parliament passed an electoral reform Act. The ancient ad hoc electoral arrangements of "rotten boroughs" and voting eligibility was replaced with a streamlined class and economic suffrage eligibility. Urban working class voters would be disenfranchised. The prosperous middle class would now dominate the suffrage. But most British statesmen would remain from the upper class. No women had the vote. Politics was almost universally considered a male domain. It was however legally possible for a non European man to vote. Slavery had been abolished in Great Britain. Heavy racism belonged to the later Social Darwinian age. Then along came the visionary, felon and adventurer Edward Gibbon Wakefield and his famous younger brothers, William, Arthur and Daniel. The founders of the New Zealand Company that brought the gleam in the eye of Hobson to the stark reality of mass British immigration into New Zealand.

Edward Wakefield. He served a three year sentence with his brother William for attempted abduction of a fifteen year old heiress. In the same era, Britons were being hanged for small thefts. They were from a distinguished family and high society seemed to consider them toads or naughty boys.

William Wakefield. He is called the father of Wellington by his leadership of the Port Nicholson settlement, and his successful campaign for the capital of New Zealand to be moved from Auckland to Wellington. Generations of Parliamentarians have privately cursed him at cold wet windy moments in Wellington.

The rat eaten and burnt original Treaty of Waitangi. Now the sacred founding document of New Zealand. Kiwis are all supposed to do obeisance to it every day.

A depiction of the Waitangi signing on February six 1840. A National holiday since 1974

A depiction of the 1840 Treaty signing road show

Treaty of Waitangi text found in a Littlewood family house drawer in 1989. It is dated February fourth 1840 and written on paper with an 1833 watermark. William Colenso, an eyewitness, records in his book, The Signing of The Treaty of Waitangi. "On the morning of February fifth at Waitangi, in an erected spacious tent, Hobson, Busby and Rev. Henry Williams were engaged in translating the Treaty." That appears to be the the Littlewood Treaty being translated into Maori and edited and expanded. Despite much academic hedging, there is no compelling reason except politics to doubt the authenticity of the Littlewood Treaty. The document itself makes eminent sense to convince the proud Northland Maori chiefs to sign a document that promised to preserve their resources won by their warrior prowess. But not to let the cat out of the bag, that they would sign away their chiefly right to practise their traditional way of life without being publicly hanged by the neck. The Littlewood Treaty writes, "The Queen of England confirms and guarantees to all the people of New Zealand the possession of their lands, dwellings and all their property". In the official Maori version, the guarantee " ki nga tangata katoa o Niu Tirani " "to all the people of New Zealand" is to their whenua, lands, their kaianga, resources, and all their possessions, taonga katoa. In the official English version of the Waitangi Treaty most likely translated from its Maori version, that is expanded to "lands, estates, forests, fisheries and other properties". There is no reference to "all the people of New Zealand". British officialdom to appease Maori and their social consciences extended recognition of all the land and water territories of New Zealand to the tribes. In the South Island, the Maori population had been by disease and the musket wars reduced to several thousand by 1840. In Auckland, Maori were likewise reduced to a few hundred by 1840. Thus did the nascent Government of New Zealand make a rod on its back in order to invalidate land speculators such as De Thierry and the New Zealand Company, and to pacify the Natives. They not surprisingly were noticing the flood of white immigrants into their territories. For the next two decades, there were sporadic "fires in the fern" between British and Maori in the Flagstaff war in Northland, in the Wairau massacre in Nelson South Island, at Wanganui and in the Hutt Valley campaign. There was nothing that wasn't eventually pacified with a combination of military action and land sales or compensation. If that aroused animosity and jealousy between tribes and individual Maoris, the aggrieved could come back for more. By 1858, the New Zealand newspapers were boasting that the first official census declared that the white population now outnumbered the Maori population. That was most likely wistful thinking. The new towns were growing rapidly and thriving. But the hinterlands were still Maori land. The boasting was a big mistake.

William Colenso. Printer, linguist, botanist and explorer, defrocked priest and grand old man in provincial politics. Born in Cornwall in 1811, he missed seeing the twentieth century by a year. His family were trades people. His cousin was John Colenso, the famous controversial Bishop of Natal. William's land explorations took him into the hinter lands of the North Island. He entered deep into the Maori spiritual and political life but always remained an upright missionary until his fall from grace. At the age of forty one, he fathered a child from his Maori house keeper. The Church forgave and restored his priesthood forty three years later. There are remarkable coincidences between Kendall and Colenso, separated in time over three decades. Both were fervent Anglican missionaries who "went native" when exposed to Maori spirituality. Both were dismissed from their positions after adultery with a Maori house keeper woman. They were both patriarchs of the Anglican New Zealand Christian Church. Abraham too had his Hagar and Ishmael. That may have crossed their minds.

The Treaty of Waitangi that gave freedom of movement and freedom from tribalism to New Zealand.

In his initial address to the Maori at Waitangi on 6 February, Hobson proclaimed. "The people of Great Britain are, thank God, free, and so long as they do not transgress the law, they can come and go where they please, and their sovereign has not power to restrain them." This is reported by Colenso. Hobson of course had that translated into Maori. The Maori chiefs at Waitangi were schooled in the Maori bible. So the Maori terms were scripture. Freedom is not an expression in the bible. So where did it find its Maori expression? Freedom translates in google Maori as Rangatiratanga. So Hobson was selling the British brand. All signatories of the Treaty would become as Britons acquire supreme chiefly power. In the Maori bible, Rangatira is the translation for God and the Emperor. The law was the Ten Commandments. Rangatiratanga was in the Treaty ambiguous from the start. The new Treaty promised Rangatiratanga (freedom of movement). Maori needn't now fear an enemy attack . But what would be the response of British officialdom if they were accused of breaking the Ten Commandments?

For the only time in New Zealand history, the Crown, the colonists and the Maoris gathered together in 1840 to freely argue out New Zealand's destiny. Only the European women and Maori slaves appeared to have no direct participatory role in the Treaty negotiations. The European women because they ostensibly stuck to house keeping affairs, the slaves because they were dogs bodies. Seven years before in 1833, slavery had been abolished in the British colonies. Chiefs were already liberating slaves who were returning to their homelands as missionaries and advocates for British colonialism. So many a slave's heart might have been fluttering in 1840.