Fighting for Modernism and the Empire

- lloydgretton

- Nov 18, 2022

- 28 min read

Updated: Nov 15, 2025

Fighting for Modernism and the Empire continues on from The Liberal Years.

Bill Massey

Trade Union Militancy

Frank S. Anthony

The Hinemoa Legend

World War One

The Armistice And The Influenza Epidemic

The Jazz Age

Katherine Mansfield

Wiremu Ratana

The Depression

John Mulgan

Bernard Shaw's visit to New Zealand

The Labour Government

Ernest Rutherford

World War Two

Bill Pearson

Inspecting the Kiwi troops in World War One. The two civilians in hats. To the left, Prime Minister Bill Massey, and to the right, the deputy Prime Minister, and former Liberal Prime Minister, Joseph Ward. Bill Massey declared, "New Zealand will fight to the last man and the last shilling". The Kiwi soldiers who mostly enlisted for a Government paid foreign holiday, would riposte. "Massey will be the last man, and Ward will have the last shilling." Massey was known for his Royalist Irish Protestant loyalty, Ward, an Australian born Irish Catholic, was known for his money wizardry.

William Massey 1856-1925. He was known as Bill and Farmer Bill in the non reverent language of New Zealanders for their leaders. They reserved their reverence for Royalty even Maori Royalty. Unlike the South Island which ignored or mangled Maori names, the North Island took Maori names and words to their hearts. Haere ra, meaning farewell became hooray in settler colloquial. Maybe that is a subtle dig for "hooray, you're going". A dead or broken thing became kamate. English names were soon abandoned in favour of original Maori names for localities. New Plymouth Province changed its name during its conflict with Taranaki tribes, to Taranaki Province. Petrie changed its name to Wanganui during its conflict with Wanganui river tribes. In both cases, they appropriated the names of their enemies. The ancestral Maoris and their idealised culture were esteemed. Those that took up arms against the Crown were also esteemed soon after the wars. Te Kooti always is controversial because of the stain of his massacres. But Titokowaru was forgotten about as "a bad dream". Turanga was changed to Gisborne because of postal confusion with Tauranga according to legend. However the massacre by Te Kooti in its locality may have made its name change to a New Zealand Colonial Secretary. The settlers quickly discovered the native names of the flora and fauna, and the mountains and rivers. They became identified with New Zealand. The Maori name for the North Island, Aotearoa became celebrated in New Zealand folk lore, music and art as New Zealand. To this day, the reputed red neck farmers of the northern Waikato are proud to say, they live in The King Country, named after King Tawhiao. The New Zealand Governor-Generals and Prime Ministers soon got a fondness for meeting Maori leaders, and sharing their hospitality in Maori traditional cloaks. Conservative Prime Ministers, including William Massey, gave a particular unction to Maori culture that was only surpassed by British Royal visitors. William named his official Prime Minister's house, Ariki Toa (Bold High Chief). New Zealand was otherwise most often a dreary land given to philistine middle class British culture. As D H Lawrence unkindly put it after a day spent in Wellington in 1922. "This cold, snobbish, lower -class colony of pretentious nobodies." This idealisation of Maori culture was not generally extended to contemporary Maoris by settler neighbours. It depended on approximation of Maoris to European living standards, and memories of the wars. Settler attitudes were particularly hostile and condescending in confiscated Maori land areas. Settlers there didn't want to talk about the wars except to cuss Maoris, like dogs with a stolen bone. The Maori King was sometimes called in local newspapers, "the nigger King". A forlorn place was described as not inhabiting a dog, nor a Maori. I recall reading that comment in my fifth form History textbook. A common joke in 1940s Taranaki was. 'If you find a good Maori, shoot him dead before he turns into a bad Maori."

William Massey was born in Protestant northern Ireland. In 1870, at the age of fourteen he emigrated to New Zealand. to join his family. His father had been lured to the northern North Island in 1862 with a Government promise of free land. He was bitterly disappointed at his arrival to find that meant bush. That is a conning tradition that goes back to the New Zealand Company. Émigrés identify New Zealand with the rolling hills and gentle rivers of Great Britain and are soon shocked with the reality. The Masseys lived on leased land in Taranaki. In Parliament, William would fight for freehold land. William was a voracious reader of English classic authors and the bible. His religion and culture was Irish Presbyterian. He became a Freemason as did many if not most New Zealand political and civic leaders. William became a leader of the conservative resistance against the radical Liberal Government. In 1894, William was elected to Parliament in a by-election. In William's own words, the telegram inviting him to contest the by-election was handed to him on top of a hay stack by a pitchfork. William served as Prime Minister from 1912 until 1925. He would remain as Prime Minister until his death as did Richard Seddon. William ranks second to Richard as the longest term Prime Minister.

Trade Union Militancy

The early 1900s was the beginning in New Zealand of trade union militancy. In particular the dock workers, mostly immigrants, had adopted socialist ideologies. The Industrial Workers of the World founded in Chicago in 1905 advocated not just improved working conditions and higher pay. Only the men who worked with their hands had legitimacy to govern as they produced all the wealth. A fairly boorish sentiment but utterly believed in as the biggest falsehoods often are. They demanded that their unions should govern their countries in industrial syndicates. The New Zealand Government was facing a challenge to its legitimacy, a great deal less bloody than the Kingite and HauHau challenges but violent and bitter indeed. Class division took over New Zealand as racial division took over fifty years before. Bill Massey never enjoyed the popular support of Richard Seddon, known by both friends and foes as King Dick. Conservatism is always on the back foot in New Zealand. The industrial workers were a large proportion of the New Zealand population, and most of the clever people have always been liberal or socialist.

Fred Evans was a militant Australian stationary engine driver in the Waihi gold mining town in the North Island Coromandel. In New Zealand legend, he is the only person killed while fighting in an industrial dispute. It used to be said he was the only person killed in a political dispute when the Maori wars were not considered political issues. The legend is he was fighting for workers' rights and was murdered. He was shooting from Union Hall at policemen and non union workers who were unkindly called scabs. A policeman struck him down and he died later. The Inquiry at Fred's death said the policeman was "fully justified in striking deceased down". Fred was given a huge public funeral in Auckland. He was celebrated as a working class hero. Militant unionist and later Labour Cabinet Minister Bob Semple declared that Fred had been "doing his duty and should have shot more." The epitaph on Fred's tomb stone seems more distant than the Maori wars. "He died for his class." "Greater love hath no man that he laid down his life for for his friends." The first quote is literal. The second is an ironical dig at the Church and any other kind of hierarchy. The miners were exploited in an economy that brought rich dividends to its share holders and imposed dangerous and dirty conditions on its workers. The Government from the Richard Seddon era were content with low taxation, and subsistence wages for the working families. By the early twentieth century, workers were feeling their power and their numbers. The modern consumer society was starting and workers wanted a bigger and fairer share of the capitalist apple. As they were fond of pointing out. Without them, there would be no industrial economy. There were more educated workers who supported the Industrial Workers of the World. Most modestly wanted to join the lower middle class of home ownership and the new consumer goods. But when they got them through industrial and political action, they became middle class, often anti-union, and aspired their children receive middle class education and professional careers.

The Great Strike was a near general strike in New Zealand from October 1913 to January 1914. It was the largest and most disruptive strike in New Zealand's history. The economy of New Zealand was brought almost to a halt. Out of a population of just over a million, between fourteen thousand and sixteen thousand workers went on strike. That statistically meant several percent of the New Zealand working population went on strike. More significant, the Great Strike disrupted and closed down the vital maritime and coal industries. The Liberal Government had become imperialist rather than reformist under Richard Seddon. Wages had fallen behind the cost of living. The Arbitration Court was being delayed in its rulings. New Zealand's international reputation as a country of workers' prosperity and without strikes became tarnished. The new Reform Government of Bill Massey was noted for a farmers' and employers' view of unions. Class division as exemplified in Fred's above grave epitaph had come to New Zealand. The street battles began appropriately over escorting race horses from Wellington port to the New Zealand Cup race meeting in Christchurch. Many a nasty class comment must have been made by the race horse owners and the workers. The New Zealand police were small sized having replaced the armed constabulary after the peace treaty with the Maori King. They were unarmed and modelled on the British police. The national myth New Zealand history was so peaceful that it never required armed police had started. In emergencies with the Maoris, local citizens were sworn in as special constables. Special constables were also employed from the countryside to crush the strikers and load the ships. The street fighting was at times vicious. Striking tram drivers rammed specials on horseback with metal spikes and detonators. The police who had been created by the Liberal Government and identified with the workers and their Labour Department were placed under a new militaristic police commissioner John Cullen and made common cause with the special constable strike breakers. The strike breakers were mostly farmers' sons, hated the unions, and were having the time of their lives. No doubt so also were the young striking workers. In the Great Strike, neither side used guns. Fred had died a martyr to stopping guns by either side being used again in civil conflicts in New Zealand with one exception. In 1916, two Maoris were shot dead in gun fire exchange with police during a raid on the North Island East Coast upon the community of the deluded Maori prophet Rua Kenana. Police Commissioner John Cullen orchestrated that too. New Zealand conservatives have never been squeamish about shooting Maori "outlaws". The special constables in the Great Strike soon got the name of Massey's Cossacks. Bill Massey became a reviled figure with the New Zealand working class. His political career has parallels with Margaret Thatcher. He created a new political Party out of conservative Parliamentarians that replaced the Liberal Government in 1912. He named it the Reform Party. The Reform Party ruled New Zealand until 1928 and in a coalition from 1931 to 1935. The New Zealand National Party grew out of its loins. His death was celebrated in workers' communities. As befitting its Reform name, the Reform Government enabled thirteen thousand Crown leasehold farmers to buy their land. The New Zealand land owning rural communities are the legacy of the Reform Government. Reform brought in a professional and ostensibly apolitical bureaucracy to replace the political machine of the Liberal Government. A story had circulated that Richard Seddon appointed a crony to the Education Department. Richard had appointed himself Minister to many Departments. A memo was sent to him. The man was illiterate. Richard sent back a memo. "Learn him." William's supporters became known as Masseyites.

A sketch by Neville Lodge which accompanied the 1951 edition of the Me and Gus stories by Frank S. Anthony. Frank was born in 1891 in Matawhero Gisborne. His family later in the 1890s moved to South Taranaki. They settled on a remote "backblocks" Taranaki settlement. They became Masseyite Taranaki "cow cockies". Frank's mother was a school teacher. His restricted hard life on their farm drove Anthony to spend most of his free time writing poems and short stories. Anthony's ear and retentive memory caught the comic vernacular yarn of the cow cockies. A habit the cow cockies may have picked up from their mostly despised Maori neighbours. Anthony's restlessness made him go a roving from 1909. From a deckhand on New Zealand coastal steamers, he soon moved to merchant sailing vessels on the Cape Horn sea routes. He joined the Royal Navy in World War One. In 1916, his lung was seriously injured in an accident on his ship. Modern wars are industrial. Their war heroes most likely are victims of industrial accidents. That repatriated him in 1918 back to Taranaki. In 1919, a soldier's rehabilitation grant enabled him to purchase a dairy farm on marginal land in Taranaki. As did most other war veterans, he struggled to earn a living. In the evenings, alone in his shack, he returned to his creative writings. His writings drew prolifically on his experiences as a struggling backblocks farmer and sailor. He sold his farm in 1924 and travelled to England to develop his New Zealand literary successes into a professional career. His writings did not fit the refined literary set in England. He died in 1927 of consumption. In 1950, his mother arranged for the hugely popular Me and Gus radio adaptions. I recall my mother sometimes chortling about listening to Me And Gus in her school teacher house in Taranaki. The Me and Gus stories were then widely read in New Zealand published editions in the 1950s.

The Hinemoa Legend

This is New Zealand's most famous legend. It is a story orally recorded before European contact. Governor Grey wrote the first version in his 1855 book, Maori Mythology. The story was told to Grey by his Maori cultural adviser, Te Rangikaheke . The full power and beauty of Maori poetry and oratory figures in this story of redeemed love between a young warrior and a maiden. I can vouch for that because I have read its Maori language version first written by Te Rangikaheke.

The story first appeared in the cinema in a now lost French film in 1913 by the French film pioneers, the Melies brothers. It was shot in New Zealand as one of four Maori exotic stories to delight Western silent cinema goers.

In 1914, the story of Hinemoa appeared again in silent cinema form. It was billed as "The first big dramatic work filmed and acted in the land of the Moa." It toured the country and was later exhibited overseas.

The romanticisation of Maori culture was now in full New Zealand and international sway. Other popular movies about Maori culture and history soon followed. In 1925, Rewi's Last Stand about the Waikato war was produced in New Zealand. A sound version of it was produced in 1940.

Hinemoa, the 1914 version.

World War One

In 1914, the European Great War later known as World War One broke out. New Zealand as a Dominion automatically joined the British side in the war. Immediately upon the outbreak of the war, William sent a telegram to the British Government. "All we are and all we have is at the disposal of the British Government." They must have been comforting words. The British Government immediately took him up on them.

I will leave World War One to much better historians than me. The most trenchant points are: Conscription was brought in in 1916. Maoris were mostly exempted. Attempts to impose conscription on Waikato tribes met resistance. Over one hundred thousand men and boys departed New Zealand for "the great adventure" in Samoa, Gallipoli, Palestine and France. More than sixteen thousand lost their lives and over forty one thousand were wounded. Counting the casualties together that makes more than one half of the New Zealand expeditionary force. However many of the men must have been wounded several times and killed. "The heroes are in the cemeteries," as old soldiers would say. Most of the New Zealand soldiers had never ventured outside New Zealand. They quickly got the reputation as good virgin soldiers. Their nickname to distinguish them from the Australian soldiers in the Anzac brigade in Gallipoli was Kiwi, the much loved flightless New Zealand bird icon. The name came from their New Zealand Kiwi shoe polish. The name Kiwi for New Zealand has stuck ever since and has grown in the 2,000s in popular usage. It denotes a hardy, practical anti intellectual people. Unconsciously, it collates with Kupapa. Both Kupapa and Kiwi denote a people that stay close to their territory, not sophisticated, and not much xenophobic. William Massey exhorted the workers in the union strikes to take their fighting spirit to the New Zealand army. They would be fighting for the British army, for their King and their country, Britain and New Zealand. The actual mood of most Kiwi soldiers might be illuminated in this story. Turkish army officers asked Kiwi soldiers why they had come such a great distance to fight them. The Turks were bemused when the Kiwis replied. So they could play more rugby.

New Zealand soldiers departing for the great adventure.

The Armistice and the Influenza Epidemic

The end of World War One was declared on Armistice day November 11 1918. William Massey in France signed the Treaty of Versailles. There were huge festivities among the victorious nations, including New Zealand. New Zealand's signing of the Treaty was the first sign of an emerging independent country. William and his deputy Joseph returned in triumph to New Zealand in time for the Influenza epidemic. Socialists blamed their ship for bringing the influenza into New Zealand. I have seen a workers' newspaper, (Truth) cartoon of William and Massey canvassing for a New Zealand election as viruses.

How the world fought the 1918 Spanish influenza epidemic. After a year, it had vanished which is the normal life cycle of a virus. In present times, these good heath publicity measures are called and penalised as conspiracy theories.

The Spanish influenza struck New Zealand between October and December 1918. It killed about 9000 people in two months. The epidemic changed the New Zealand culture. Death ceased to be a cultural event and became a trauma and an amnesia. So many died that New Zealanders ceased their regular visits to their loved ones' cemeteries. The dead from the war also affected the national psyche. But they were war heroes resting in military cemeteries overseas, and memorialised in every urban centre in New Zealand. After the influenza, the people stopped talking about it, or maybe even thinking about it. Maori villages were wiped out by the influenza. Maori however and more working class others kept up the tradition of cemetery visits. This is now seen as uniquely Maori culture.

The Jazz Age

New Zealand was now in the jazz age. So many had suffered in the war and epidemic, that a mood of materialism and pleasure seeking took over the country. Many still regularly attended Church, and Christian morality ruled social and private life. But many, especially youth, craved for novel entertainment in the picture theatres, radio, and the modern music of the dance halls. They invaded every European community in New Zealand. Maori remained in their villages in their pre modern rural life styles. Most now spoke English as at least their second language. After the wars, Maori leaders had fostered Native schools to draw Maori into the modern world.

Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield 1888-1923. New Zealand short story writer, poet, essayist and journalist. Looking suitable bohemian or typically unkempt expatriate Kiwi.

Kathleen Beauchamp was born in Wellington in a wealthy banking family. Wealthy that is by New Zealand colonial standards. She attended the elite Wellington schools where her soul mate was Maata Mahupuku. Maata is famous as Katherine's muse. Their relationship recalls the 1954 Christchurch high school murderers Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme. Juliet also grew up to become a famous author However whatever dark school girl fantasies,Kathleen and Maata held, did not develop further. Kathleen was headstrong and loved to explore the untamed New Zealand terrain. When Kathleen was nineteen, she went on a camping trip into the Ureweras, the rugged hinterland of the North Island. Out of that experience, she wrote her short story The Woman At The Store about an undisclosed murder. I taught that story to my class at a Chinese University. I told my students, I suspected Kathleen really had stumbled upon a murder she did not report. I also warned my female students not to go out camping and drinking alone with boys. Unable to attach herself to parochial dull middle class New Zealand, Kathleen still nineteen departed to England. In England, she published her writings as Katherine Mansfield. Mansfield was her second name. This has been a common trope of New Zealand intellectuals. New Zealand is or was a great place to grow up in. So raw and empty is the land, that the childish imagination is given full rein. Then one grows up and looks around. Where are the cultural centres? Where are the people? The latter question was asked by an English literary critic about Katherine's short story, At The Bay. The New Zealand intellectuals who could not escape New Zealand mostly have either gone mad or developed an infatuation with Maori culture as Acadia. The latter was harmless until Maori radicals adopted and weaponised it.

In England, Katherine looked back to her New Zealand childhood and published her famous stories in the literary modernist movement. Wikipedia says her writings "explored anxiety, sexuality and existentialism". She became friends of the literary Bloomsbury Group that included D. H. Lawrence and Virginia Woolf. Her character appears in several of Lawrence's novels. Katherine had a genius talent to recall childhood experiences and transmute them to literary gold. As with so many bohemian authors, including Lawrence, she died in early middle age of tuberculosis. She married in England a friend and rival of George Orwell, John Middleton Murray.

Te Ua Haumene. Te Ua was born in South Taranaki in the 1820s. As a child he was taken as a slave to Waikato. There he received Christian instruction and baptism by the Wesleyan Mission. He became a Wesleyan mission teacher in Taranaki in the 1840s. He became an enemy of the Government in the 1860s Taranaki war. He baptised the second Maori King giving him the name Tawhiao. In 1862, Te Ua had a vision. Well versed in the Book of Revelation, he was instructed by the archangel Gabriel to lead the Israelites, his Maori people, in casting out the yoke of the Pakeha. Then all the unrighteous, presumably the Pakeha, would perish. He called his cult HauHau, from Te Hau the spirit and wind of God. Pai Marire (goodness and peace) and Hauhau became interchangeable names for this cult. His followers would dance around flag poles shouting in tongues, mostly random English words and phrases unintelligible to them. They believed when they charged into battle, chanting HauHau with their right arm aloft, they would not be harmed by bullets. They were also known to emit dog like barks. Heads of British soldiers were preserved. Captain Lloyd's head was carried around the North Island as endowed with prophetic powers. A missionary, Volkner was murdered by the Hauhau. He was hanged in a tree, his eyes cast out and swallowed, his blood drunk in a chalice cup in a Church. In 1866, Te Ua capitulated to British forces. Governor Grey declared Pai Marire "repugnant to all humanity". Te Ua was paraded through the North Island by Grey and imprisoned on Kawau Island. Te Ua declared it was all a dream. He died that same year. HauHau was taken up by fanatic elements. Every troublesome Maori came to be known as Hauhau until the turn of the century. But the good and peaceful Pai Marire has survived in the later Maori prophets from Te Kooti to Brian Tamaki, the rebel against the Covid regime. HauHau is characteristic of tribal prophetic movements who in despair at their extinction to modernism return to their pre modern cultic practices and are accordingly cursed and exterminated by all civilised peoples. The most recent manifestation has been Islamic extremism.

Old Maori fulla, Wiremu Ratana. He was known to his mates, as cheerful Bill Ratana who loved a good party. Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana was the founder of a Maori religious movement which, in the late 1920s, also became a major political movement. He was the latest in a line of prophetic descent which began with Te Ua. Wiremu is believed to have been born in 1873, in the North Island. His grandfather owned a prosperous sheep and cattle station. After the influenza epidemic, Wiremu became his sole surviving male heir. Wiremu's family were distinguished with both Europeans and Maori as Methodists, faith healers, and herbal medicine dispensers. Wiremu was thus exposed to strong but diverse religious and political influences from his childhood. Wiremu after an elementary school education, worked as a farm labourer. He was keen on rugby and race horses and was a champion ploughman and wheat stacker. At the turn of the century, Maori were assimilating into the working and leisure world of the New Zealand working class. Thanks to dedicated Maori leader support, and European teachers in the Native schools, they were now blessed with bi-lingualism.

In 1918 while ploughing, he saw a cloud approach like a whirlwind and give him visions. After Wiremu reported that experience, he became regarded as the Mangai, (mouthpiece) of the Holy Spirit. That day became celebrated as the anniversary of the founding of the Ratana Church. He prophesied those who would die of the influenza. Those who left their homes to follow him, survived. His wife and family who had believed him mad, now believed him divinely inspired.

Wiremu began to show an ability to heal through prayer. His son expected to die from an infection, made a miraculous recovery after his father's prayers. By the end of 1918, a growing number of visitors came to Wiremu's farm to receive prayer and healing.

In the following three years, Wiremu rose in reputation and fame throughout New Zealand. After his cures of Europeans, his fame spread overseas. A makeshift village to accommodate his followers grew up around his home, to become known to this day as Ratana Pa, the headquarters of the still thriving Ratana Church. Ratana became known in the press and books as "the Maori Miracle Man". During Ratana visits throughout New Zealand, the majority in Maori villages became moreru (survivors) followers of the Church.

Wiremu traveled overseas to England, America and Japan to spread his message and urge ratification of the Treaty of Waitangi. By now the Treaty of Waitangi, a half forgotten and mostly ignored document among the Europeans, had taken on mystical and cultural identification powers. Wiremu failed to meet King George V. Wiremu's petition to the King however contributed to the New Zealand Government establishing a Royal Commission to pay compensation for the confiscated Maori land. With this compensation money, The King movement purchased farm land to restore their capital at Ngaruawhia. After his very successful visit to Japan, Wiremu proclaimed the Japanese and Maori as among the lost tribes of Israel. Back in New Zealand, the Ratana Church became suspected to be secret agents for Japan. During World War Two, rumours abounded that Ratana communities were in secret collusion with the Japanese Empire.

Wiremu often was accused of being a charlatan and his healings frauds. There was however the famous case of Fannie Lammas. She, an English lady in Nelson, wrote to Wiremu in 1921 to cure her complete paralysis. After she received his letter reply, she prayed as instructed. Nineteen hours later, she rose from her bed completely cured. Cynics say it was through auto-suggestion. Wiremu's healing reputation waned and disappeared. He became more political and publicly supported the rising Labour Party. Ratana candidates endorsing the Labour Party won all the four Maori electoral seats. The last Maori Parliamentarian to lose his seat to a Ratana was Apirana Ngata in 1943. When I was growing up on the East Coast in the 1960s, Apirana Ngata was the Maori giant even celebrated alongside Maori sportsmen by Maori school students. In 1936, Wiremu met the new Labour Party Prime Minister, Michael Savage. Wiremu presented Michael with three huia feathers, representing Maori. Protruding from a potato, representing lost Maori land, a pounamu (greenstone) representing Maori mana, and a broken gold watch representing broken Crown promises. Michael nodded assent. Labour Party Ratana members would hold all the Maori electoral seats after 1943 for the next fifty years. They would be taken entirely for granted as Labour Party fodder. Wiremu died much venerated in 1939.

Wiremu Ratana's life and career has striking parallels with his American contemporary Edgar Cayce. Both were born in poor rural communities and had elementary education. Both won their great fame as healers and clairvoyants after the mass deaths and traumas of World War One and the influenza epidemic.

The Depression.

On October 24 1929, the New York Wall Street stock market crashed. Unlike the global capital casino of the last four decades, world wide capital in 1929 was inseparable from wealth production. Also, there was no or very miserly State welfare. If you became unemployed without other means of support, you went hungry, lost your home, your clothes fell to pieces. Within a year or so after 1929, the Depression hit New Zealand. The towns became full of hungry people wandering around aimlessly. Prices fell. So if you kept your job, you might never be so better off. However, the employers might reduce wages and dismiss their workers any time. My mother, born in 1926 in a middle class professional family, never heard about the Depression until after it was over in 1939. My father born in 1918 on a family dairy farm lived a life little different from nineteenth century European peasants.

A 1932 Wellington Depression riot. The workers fighting for work according to the Socialist press or hoodlums fighting the law according to the capitalist press. Literature and folk legend propagate the former narrative. The latter only appears in newspaper archives.

John Mulgan was a New Zealand writer, journalist and editor. His most famous work is his 1939 novel, Man Alone. This opus gave a literary foundation to the image of the strong, practical and silent Kiwi male. A genre grew out of it, as popularised in such authors as Barry Crump two decades later. Socialism came into New Zealand in the 1935 election. But for most Kiwis, it was peripheral to lives still harsh and unforgiving both in nature and society. John Mulgan was a scholar and a soldier in World War Two. He committed suicide in 1945 in Cairo. That remains a mystery. He waged guerilla war in Greece against the German occupation. The German military knew him as a terrorist. Nor would all Greeks have celebrated him. That might have plagued his mind. In the temper of the time, no newspaper or book considered that. In Man Alone, the unemployed young men leave in 1934 their work camp to join the Queen Street workers' demonstration.

"Robertson refused to come. Sitting on the edge of his bunk he had watched them get ready. ...

"You had better come, Mac," he had said. ... "They'll see they can't treat us like dirt, they will."

"That's what ye are," Robertson said, rolling a cigarette. ... "That's all ye are. Just dirt.

Scotty in Man Alone was an unemployed Social Credit man. From the 1930s, money reform loomed large in the working class discourse. People were desperate or desperately afraid. Working people read about money reform. When Social Credit English reformer Norman Douglas visited New Zealand in 1934, he packed out the Auckland Town hall. By 1978 only one other foreign speaker, Bob Hope could do that. Bob's best joke unconsciously summed up Social Credit. "Banks only lend you money when you don't need it." Social Credit ranked third in New Zealand political Parties after Labour and National. After 1984, it sank into clownishness and mergers with other minority Parties. It had several Parliamentary members, despite First Past the Post in elections. It unsettled the two major Parties and was at times considered as a future Government. Its popularity was drawn from disenchantment with the major Parties and its promise of cheap and easy bank credit. Its theories were beyond public comprehension. It accompanied economic theory with naturalism. It was identified with eccentrics who were known to engage in nudism and own small businesses that promulgated their theories. The capitalist media effectively stuck on them, the Orwellian label, Funny Money. Its voters in the 2020 election numbered a few hundred according to the voting machine tally . As an old Social Creditor said. "What's Social Credit?" The public prefer The Apprentice with its catch cry. "You're fired."

My Amazon paperback and kindle novel, Tom Murphy, is set in the depression years' history.

In 1934, Bernard Shaw made a one month visit to New Zealand. Here he is with his twinkling eyes with nurses at a Karitane babies' hospital. Doctor Truby King founded the Karitane homes from the early 1900s to provide State support for both indigent and middle class mothers. The last Karitane home closed its doors in 1980. No official reason appears to have been given for ending an eight decade practise of the much loved frequent Karitane visits to new mothers' homes, and the baby hospital care.

Bernard's visit via HS Rangitane from London to Wellington caused huge public excitement reminiscent of Mark Twain's visit four decades before. Bernard came to New Zealand to see socialism in action. Three years earlier, he had likewise visited Russia. In both cases, Shaw wore rose tinted glasses. The privileged classes lived comfortable lives in lands with very low cost of living and crime. But the bottom classes, peasants and workers in Russia, unemployed and indebted farmers in New Zealand, lived miserable lives. Bernard was feted by the leaders of both socialist laboratories. Crowds greeted the world's foremost public intellectual wherever he traveled through the tourist attractions throughout New Zealand. "If I showed my true feelings I would cry," he told a photographer on board the Rangitane who had asked him to give his brightest smile on leaving New Zealand. "It's the best country I've been in." Bernard congratulated New Zealand for bringing in socialism "peacefully and reasonably". He donated his book collection on the Rangitane to the Turnbull library, including Mein Kampf. His words in New Zealand now appear prophetic. He urged New Zealand to be self sufficient, not to expect the "special relationship" of non tariff trade with Britain to last the twentieth century. Not to become too reliant on tourism which would turn Kiwis into hoteliers. That actually happened to the tourists. He recommended the creation of a New Zealand film industry "or you will lose your souls without even getting American ones".

The Second Coming. The Cabinet of the new Labour Government in 1935. The much longed for workers Government had arrived. Not a woman or a brown face in sight. All in business suits. According to legend, Robert Semple seated at the far right bought his first suit for the official photograph. The New Zealand workers consciously made themselves a class. Most lived simple lives of toil and pub. A minority went regularly to Church. Anything more educated was termed toff or swell for which they wore their best clothes and imitated middle class manners. These men were expected to usher in for the workers and their families, a new society "from womb to tomb". As John A Lee, a prominent Labour Parliamentarian waggishly put it. "From erection to resurrection." The workers' leaders in the Labour Party and the trade unions read and reread a small number of books as left wing holy writ. The books taught them capitalism and capitalists were cruel and backward. They would displace them with Socialism as secular Christianity. In 1938, the Labour Government brought in the Social Security Act. No one need starve in in Gods' Own Country as their Liberal hero Richard Seddon had trumpeted. Richard had meant prosperity in a land of permanent full employment and high wages. The Depression had shown that was not permanent in a modern industrial economy. The Government aimed to make it permanent with its new Social Security Tax augmented with new Government loans. The London banks demurred on the new loans. Without the London loans, the Social Security Act was unaffordable. Communism or Fascism beckoned. My father had two older brothers and a sister. One brother and the sister became Communists, the other brother became a Fascist. But then came 1939 and the European war, soon to be World War Two. New loans were immediately secured in return for New Zealand primary products, and the next generation of young New Zealanders' war adventures and blood.

Michael Savage, the Australian born Labour Government Prime Minister 1872-1940. To Labour Party supporters, the uncharismatic Mickey Savage as all named him, was a secular God. He moved his former landlord and lady to his Prime Minister's Residence to be his house keepers. Thousands would gather at railway stations to stare at him. A public honour formerly reserved to Royalty. Royal portraits characteristically hung in Government offices. Micky Savage portraits characteristically hung in workers' homes. Royals' and Mickeys' faces both gave solace. At his State funeral in 1940, there was public mourning akin to the death of the Sovereign. In the 1938 election, the Labour Party won the great majority of Parliamentary seats and most of the votes. My mother was eleven in a select Wellington school. She recalls the excitement of that election. Her much loved teacher taught his class, the Labour Party were saintly and the conservative new National Party were devils.

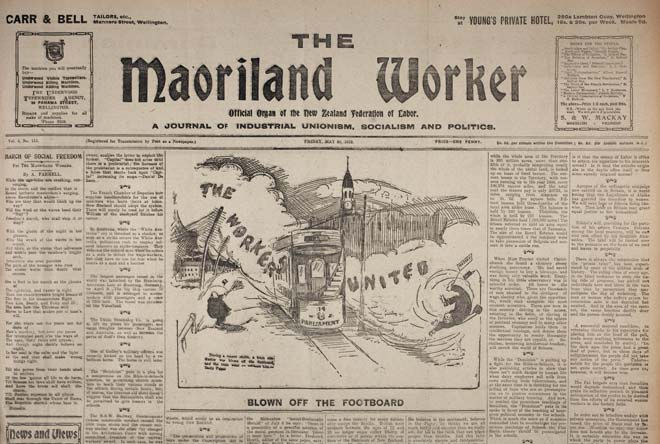

The Maoriland Worker was the newspaper of the New Zealand Federation of Labour who were known as the "Red Feds". The federation represented the more militant trade unions.

The newspaper was the workers' and their unions' refutation of their image in the capitalist newspapers. The Maoriland Worker was first published in 1910 and began as a forum for a wide range of left-wing views. Truth newspaper in the same era was scarcely less pro worker but it was also salacious. Workers were characteristically socially puritanical at least in public. The name Maoriland reflected the Australian origin of its original Australian publishers. To non New Zealanders, New Zealand remained still popularly viewed as Maoriland. But no longer the land of treacherous cannibals. New Zealand was the land of brown flax wearing singing natives, especially in Rotorua. When Richard Seddon visited the Queen in 1897, he was advised to wear his native dress to thrill her. Most New Zealand workers knew little about Maori and judged them as precursors to themselves as victims of capitalism. In 1913, The Maoriland Worker had a circulation of 10,000 copies. This cartoon on the front page of this 1913 issue suggests that the combination of the moderate and militant wings of the union movement would create an unstoppable force. The mighty gust of workers' unity blows anti-union Prime Minister William Massey off the footboard of the tram of Parliament.

Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both atomic and nuclear physics. He is reputedly "the father of nuclear physics". I grew up with the notion of Edmund Hillary, as the greatest he man for first climbing the world's highest mountain, and Ernest Rutherford as the greatest scientist for splitting the atom. Wikipedia says two other scientists working under his direction split the nucleus. His face is on New Zealand's highest money denomination.

Ernest's birth and upbringing in New Zealand is the story of the South Island pioneering families who out of a wilderness built a first world nation starting from two decades before his birth to his death in 1937. His father was an artisan and his mother a school teacher. He was buried in Westminster Abbey near Charles Darwin and Isaac Newton.

World War Two

Peter Fraser. The dour, myopic, Scottish Socialist Prime Minister 1884-1950. As with Mickey Savage, Peter Fraser began his New Zealand career as an Auckland labourer. Mickey was a brewery cellar man. Peter was a dock worker. In both cases, their careers progressed via militant trade unionism. Unlike the rather simple Mickey, Peter was a bookish intellectual. A virus in his childhood damaged his sight and stopped him getting a professional career. In England during World Two, he mortified his advisers with a history monologue at Oxford University. Upon being appointed Prime Minister in 1940, Peter that year introduced military conscription. Mickey had kept his benevolent public image to his death.

In 1947, the New Zealand Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act. This removed the Crown prohibition on New Zealand repealing or altering its Statute of Westminster Act 1931. According to the New Zealand Parliament website, "Full New Zealand sovereignty can therefore be dated to 1947". The 1931 British Statute of Westminster had granted "complete autonomy to its six Dominions," including New Zealand". When Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, New Zealand declared war immediately after. However, nearly everyone assumed New Zealand was at war at the immediate moment of Britain's declaration, as in World War One. My father said he was told by his family, Mr Chamberlain's declaration of war. Dad went outside and chopped down a tree. 1947 was the same year as India's Independence Day. In New Zealand, no one danced in the street nor rioted. As I explained to the Indian boy in my school class in China. "Before Independence as British citizens we were big big big. Now we became small, small small."

The Maori Battalion performing the haka (war dance) in the desert. Maoris were not conscripted in World War Two. However historical grievances were set aside, as young Maori men flocked from their villages to join the fight for glory and equal citizenship. Maori warrior tradition was to stalk, and only to attack when fortune favoured. But these young men appeared to have swallowed the European legend of the daring and chivalric Maoris. In consequence a few months after this haka, many of these young men were dead and wounded.

105,000 men and women auxiliaries from New Zealand served overseas during the Second World War. Over 11,000 died, nearly 16.000 were wounded. After World War One, statues of the soldiers with their listing of their dead occupied every town and district in New Zealand. After World War Two, memorial halls were erected instead. The ANZAC landing in Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 has been made from 1916 a public holiday. In 2010, in a backpackers I overheard, "Why are people walking around in the street wearing paper flowers". In the Covid era, the two World Wars have been propagated by the rebellious as wars for freedom. "Freedom" is inscribed on the war statues. It is now a seditious word.

Because of the great distance from the battle fields, the New Zealand soldiers only came back on one furlough. The war created an alienation in society. The men became hardened soldiers. Civil life back in New Zealand made them "restless sleepers" Their wives and children experienced their oppression in drunkenness and abuse. When the soldiers came back on furlough, they discovered war profiteers had taken over. The country was under heavy censorship. Peter Fraser who had been gaoled in World War One for sedition in particular for opposing conscription was now enforcing an even harsher conscription. To the Labour Party leaders, it was easily explained. This time they were fighting for Democracy and Socialism, not for the Empire. To the soldiers, their toil and wounds were the same. 500 soldiers on furlough traveling back to the war refused to disembark from their train. They were released and court martialed.

Post War Fretful Sleepers

"There is no place in normal society for the man who is different," wrote post war veteran, author and critic, Bill Pearson1922-2002. In 1952 Bill' essay Fretful Sleepers was published in the New Zealand literary magazine Landfall. Born in the South Island, Bill grew up in Depression New Zealand. His family were working class but Bill's father remained employed as a stationmaster. Bill was homosexual. So all his life until his middle sixties, he was forced to live furtively. In 1954, Bill chose to return from England to New Zealand. Bill sincerely disliked New Zealand. Its disdain for high culture. Its cheap copies of American culture. Its contempt, except for public show, of Maori culture. New Zealand was his home. My Chinese wife said to the Chinese police woman. "When Lloyd learnt he was returning to New Zealand, his eyes filled with tears."

To be continued in my blog: Giving Socialism A Human Face

.

Comments